Michigan State University builds global slave trade paper trail

How Michigan State is compiling the global slave trade's paper trail

3/11/2018

Dean Rehberger is the director of Michigan State's MATRIX and part of a team compiling a slave trade database.

The Blade/Brian Dugger

Buy This Image

A drawing by Jean Baptiste Debret of laborers selling goods in Brazil.

EAST LANSING, Mich. — An 1853 newspaper ad placed in Jornal do Commercio by Brazilian entrepreneur Damaso Antonio de Moura was the final piece to a puzzle that had perplexed Maryland history professor Daryle Williams for months.

The ad in the Brazilian publication sought help in tracking down a runaway slave named José Congo, who had a wooden leg. Using the biographical information in the ad, Mr. Williams identified him as a man who was enslaved in west Africa in 1833. The man was illegally trafficked to Brazil, where he eventually had his leg amputated and replaced with a wooden peg leg before escaping.

“You can see the excitement in Daryle. It’s like detective work,” says Dean Rehberger, the director of Matrix: The Center for Digital Humanities and Social Sciences at Michigan State University.

Mr. Williams excitedly recounted his research findings while videoconferencing recently with Mr. Rehberger and Walter Hawthorne, chairman of the Michigan State’s department of history.

José’s story is the latest research to be added to “Enslaved: The People of the Historic Slave Trade,” an online hub of worldwide slave trade data being developed at Michigan State by Mr. Rehberger and Mr. Hawthorne with the help of a $1.5 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. More information can be found at enslaved.org.

VIDEO: People of the Historic Slave Trade

There are eight main collections of data on the global slave trade that existed from the 16th to 19th centuries: at Michigan State; Harvard University; Vanderbilt University; York University; University College, London; University of Colorado Boulder; Emory University, and the work led by Mr. Williams at the University of Maryland. The challenge is for Michigan State to connect and organize the collections to allow students, researchers, and the public to easily search the data to understand and reconstruct the lives of those who were part of the slave trade.

“Slavery had a profound impact on the world. It has shaped the world we live in today, especially when you think about the racial tensions and inequality that exist,” Mr. Hawthorne says. “This will be a tool not only for scholars but also for the general public. Genealogists, K-12 teachers, anyone in the country who has the ability to connect to the Internet will be able to use it.”

The breadth, complexity, and facts of the slave trade are not understood by many people. More than 12.5 million slaves were put on slave ships, but only 10.7 million survived the voyage to the Americas. Fewer than 500,000 disembarked in what is now the United States. About 10 times as many slaves were sent to Brazil, essentially building Brazilian society and its economy. Twice as many slaves were put to work in Haiti as in the United States.

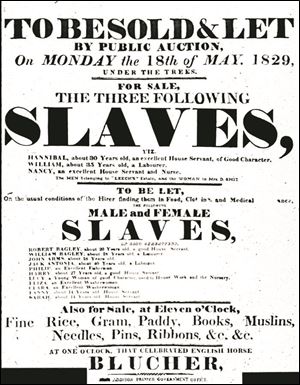

An advertisement for an 1829 slave auction. Documents such as this make it possible to trace the lineage of the descendants of slaves.

“Everything that was built in the Americas between the 16th and 19th centuries was a product of slave labor,” Mr. Williams says.

The effect devastated African societies and economies, particularly in central and western Africa. Kingdoms warred against each other to capture prisoners to be sold to European slave traders. Women of child-bearing age and healthy males were ripped from villages, making it impossible for stable economies and healthy societies to develop. Those who weren’t captured went on the run to avoid becoming enslaved.

Slaves were stripped of their dignity but not their identities.

“It is awful to say, but slaves were objects and property, so the traders kept records of their objects,” Mr. Rehberger says.

Captains of slave ships kept logs with numbers of occupants and details about transatlantic voyages, including illnesses that may have swept across the ship’s population. The clues left behind turn into a series of dots that need to be connected by historians.

“The ships’ captains kept detailed shipping records with the names of the slaves. But there were other institutions that had records. The Catholic Church wanted everyone to be baptized, so slaves were baptized. You can find their baptismal records with their given Christian names,” Mr. Hawthorne says. “The institution of marriage was also important for the Catholic Church, so now you have baptismal and marriage records. When they then had children, you then had birth records, which had names of parents and godparents.”

Newspaper classifieds were filled with ads about runaways, including physical descriptions of the slave, his skill set, his guardian’s name, and the amount of the award for his return.

This left a treasure trove of data for historians and sociologists.

“If you have a spreadsheet with data on thousands of slaves, you can draw patterns; for example, males running away versus females running away. What were the marriage patterns?” Mr. Hawthorne says. “There were slave societies with slaves around, such as Michigan and New York. Then there were slave societies, where the entire society and economy were driven by slavery. So this data is key to understanding those societies.”

If Michigan State is able to successfully build a hub for all these data, genealogists and educators will have previously unavailable information available at their fingertips.

“They will be able to go in to [the portal] and search for a name, maybe someone they know, or maybe even someone famous,” Mr. Williams says. “Or they will be able to enter dates, such as 1810-1812, then search for boys under the age of 10, and they’ll get a lot of names. Then they will be able to build personal stories with those names. And there will be compiled stories available [for educators] too.”

It would be possible for a person today to trace back their family history in America to a specific slave ship. Researchers can also trace the activities of specific slave ship captains and the plantation owners who purchased the human cargo.

The eight large collections of data will be the focus of the initial phase of the Enslaved project. But later phases will add in additional collections from other sources.

“This is going to be an ongoing project. Twenty years from now, we will still be adding data,” Mr. Rehberger says. “This is a complex computational problem, but what I’ve come to appreciate is that we can bring people back to life and tell their stories.”

Contact Brian Dugger at bdugger@theblade.com or on Twitter @DuggerBlade.